Michael Frost recalls his time at Warsash in his new book "School Days, Neither Dotheboys Hall

nor Tom Brown’s’

Michael Frost spent his early days after leaving school in the Merchant Navy, working as a navigation officer for P&O. Upon leaving the sea he married and settled down in Canada, where he studied to become a lawyer. Since he retired in 2014 he put pen to paper to record his life for his five grandchildren.

He realised that his first book

"Voyages to Maturity Seven Years before the Mast with P&O"

was incomplete, missing out on personal details of his early life.

His book "School Days" tells the story of his early school days but moves forward to his cadet training at "Warsash - School of Navigation".

I hope you enjoy this brief extract from his life story.

Starting life at a new school was nerve-wracking enough in itself, but now I was definitely entering a new world of personalities, discipline and knowledge. What was to follow was obviously going to be difficult, but everything that I had learned to that point had served to make me believe that almost every challenge could be conquered if approached with fortitude. However, the acute differences between some of the cadets were to me newly important factors, so assimilation would be an issue that I had not to that point experienced: even the first language of many was something other than English, as were, additionally, their varied sensibilities.

The first introduction was to my cabin mates. The building that accommodated the cadets bore the appearance of an old army barracks. A long, drab two-storey building, it was divided throughout into rooms (cabins) of about 400 square feet apiece, into each of which 6 boys were shoe-horned. Each unit comprised as its leader a 2nd-term Junior Leading Cadet (JLC), two unranked 3rd- term students, one unranked 2nd-term, and two 1st-term cadets. In separate rooms there resided 3rd-term Senior Leading Cadets (SLCs), and above them Cadet Captain (one Chief, another in charge of Boats, and some Senior and Junior Cadet Captains (SCCs and JCCs)). The hierarchical structure was very much in the style of a seagoing ship, where a command structure was of necessity strict and uncomplicated, though here it was of course greatly compressed. (I had no difficulty in accommodating myself to this structure, for although much more complex, the deferential behaviour to others was much as it had been at my earlier boarding schools, perhaps the major difference being that here an esprit de corps was centred on the cabin, only a cadet’s secondary allegiance being to his year’s companions as a whole.)

My cabin mates, I soon found out, were a very mixed group. The JLC was a small and rather overwhelmed individual named Stewart. Although by virtue of his rank, he was ‘in charge’ of the collective cabin, I did not see him as being very authoritative (not that he had much power in that position, for his main responsibility seemed to be to keep the cabin neat and tidy: every three days there occurred very strict inspections by the cadet captains, and then once every so often there was an unannounced and very detailed inspection by the Captain Superintendent (Captain Stewart) a grimly imposing person of whom to that point I had no knowledge): cleanliness was not next to godliness ... it was godliness! Michael Frost a young Merchant Navy officer

The seniors were by this time doing little more than taking more advanced lessons and otherwise marking time, for by then most had selected the shipping companies for whom they were to work in some 3 months’ time. The first that I met was a fellow named Morris, a surly chap who rarely smiled and indeed seemed to live in his own quiet world of a lack of interest in virtually everything around him. He rarely spoke and I later felt that after living with him for 3 months, I knew him no better than when we had first met.

This was not the case with the other senior cadet. This gentleman was not like anybody with whom I had ever before coming into contact. His name was Al-Husseini, an Iraqi of formidable mien and possessed of a short temper.

Big, hairy and brutish, I found that unfortunately, he occupied the bunk immediately beneath me, ‘unfortunately’ because he delighted in kicking upwards into the plywood that supported my apparently wooden mattress. He was heavily built and well-muscled, as I quickly realized, and it was only a day or two later that I discerned that I would have to deal with this oaf, a prospect to which I did not look forward: it was evident that Stewart exerted no influence whatsoever over the fellow. I was therefore obliged to confront him one morning and, coming right up to him, told him that I would give as good as I got if he didn’t stop kicking my bunk. The result was unexpected: he said “OK!”. (One has to learn these lessons sometimes over and over again: Malfoy at Westbrook was about as tough as candy floss when it came to it, a big day-boy thug (named Fox ... nobody called him ‘Foxy’) at Cranbrook had similarly caved when confronted, and Al- Husseini taught me the lesson again. However, I should add that we never became in the least friendly: I believe he thought I was favoured by a ‘golden spoon’ – he was on a program offered by the British Government to nations whose Merchant Navies needed development. Lest I leave the wrong impression, however, it should be noted that one of the JCCs was another Iraqi, a ‘gentleman’ in every respect and one who could plainly look forward to a good career, either at sea or indeed anywhere else he might choose).

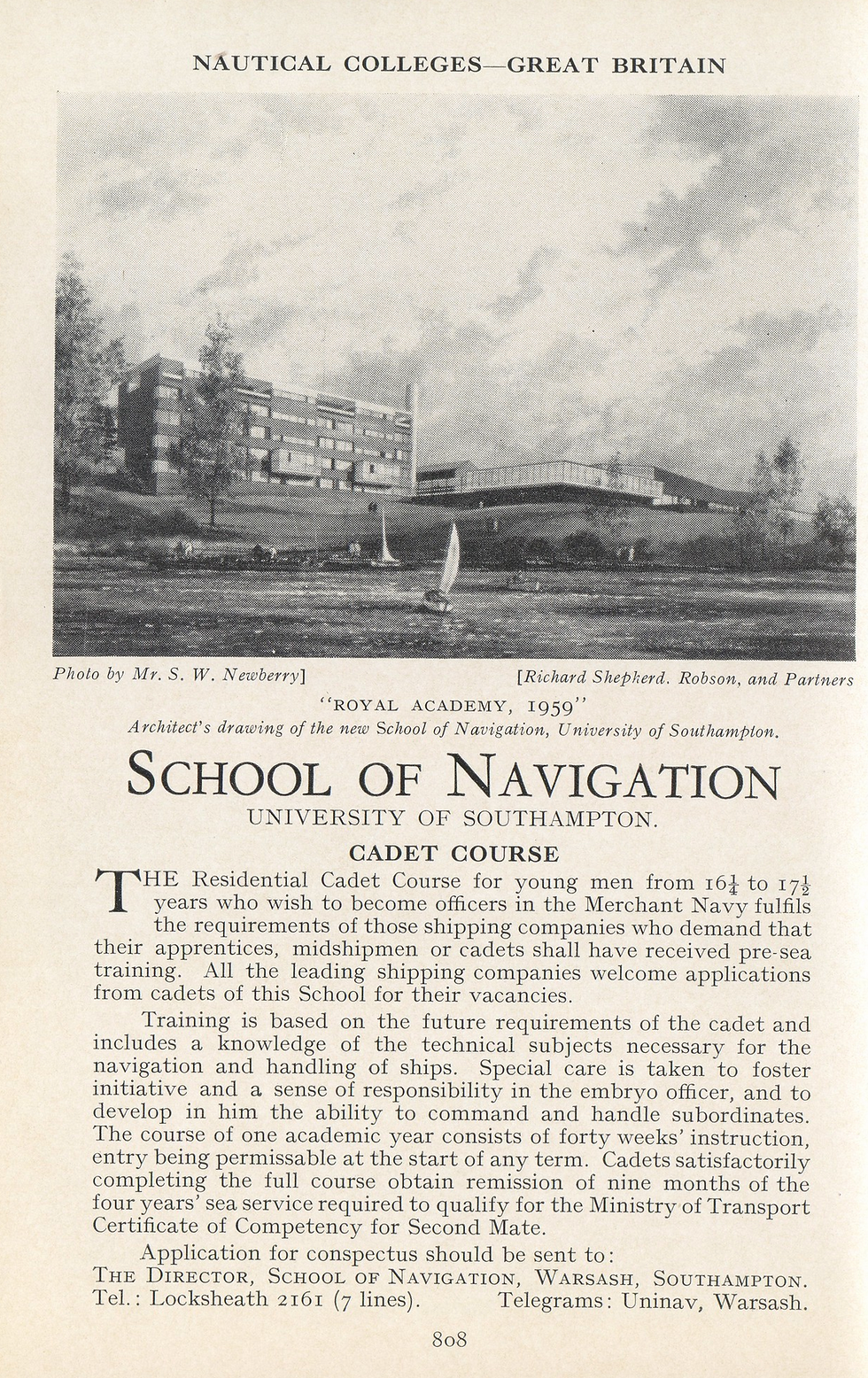

Warsash School of Navigation - Before redevelopment took place.

I discovered early on that some of my preconceptions were not just misguided, but manifestly wrong. The education that I had already experienced was good (though I soon discerned that given the sacrifices of my parents, it was not as fine as I had earlier thought); in particular I had initially felt that what I had experienced made me somewhat ‘better’ than my companions. This belief I found to be quite wrong. Certainly, I was running up against some dorks, but those characterizations had nothing to do with upbringing or schools. This school was to be my learning process about the diversity of ‘people’, neither prior school having been in the least diverse.

That this was not a public school was made immediately apparent on the first day. We were aroused at 6:30 by a bugler, somewhere out on the muddy foreshore, sounding ‘Reveille’, the traditional “wake up” call for the military (and, probably not coincidentally, for prisons!). We had about two minutes to get on running gear, sprint out to the parade ground (here, everything other than eating was done at the double) line up to be counted and then go for a road run up to the (at that time of the morning) not very quaint village, rain, wind, snow or shine notwithstanding. We then doubled back for cold showers. (There was here, however, a saving grace I had not before encountered: an antique coffee machine. For sixpence I could get hot coffee ... well, sometimes, for the machine had a major flaw: the mechanism often missed grasping the cup, so altogether too often I was faced with a scalding flow of (actually, quite awful) coffee that either splashed onto the concrete, burned the hands, or overflowed a toothmug that I would sometimes when I remembered, bring as a back-up.) This (the run, I should clarify) was not too bad in the Autumn and Spring, but horrible in winter. No time was then to be lost in getting into uniform, doubling to the refectory, and then assembling for inspection on the parade ground.

Warsash Cadets

After the morning inspection, the flag was run up the mast and the duty officer and the CCC inspected each cadet. And this was no joke either, one officer in particular (‘Jacko’, as we called him) taking a curious and frequent delight in declaring a cadet’s neck to be dirty and worthy of 2 hoursdrill, an unpleasant punishment which entailed heavy drill under Nelson’s stern eye when the rest of us were gleaning some needed respite from classes or parades.

Then came half an hour’s signals practice (Morse code and semaphore), again on the parade ground, not too arduous an exercise once one could distinguish dots from wavery dashes, followed by the classroom, which actually provided some needed physical relief.

The ethos of the training which we were undergoing was set out in ‘Principles of Training’, a document which all parents and cadets were required to certify that they had read and understood. It is worthwhile to quote a portion of its content:

“The Merchant Navy is ... very different from the Royal Navy ... the Merchant Navy motto is “Arrive safely and deliver your passengers and cargo in good order.” It is on the officers and men of our merchant ships that so much of the future of our country depends, because the efficient movement of our sea-borne trade governs the lives and livelihood of us all. Merchant seamen have to meet all races in the business of commerce without the protective coat of territorial immunity which covers the courtesy visits of our armed forces ...

“Character training is therefore considered to be by far the most important part of a course which tries to prepare a boy for life at sea ..

“Our country is widely judged by the officers and cadets of our merchant ships, and it is essential that they should have high qualities of integrity, tact, loyalty and efficiency, combined with the will to stay at sea and be happy in their profession.”

Today, these words might sound to our cynical ears more than a bit pompous, or even from a different age. But in the day when the world’s biggest shipping conglomerates were mostly British, and the Royal Navy, despite having suffered so much in the century’s conflicts, was still the second most powerful of the world’s navies, they resonated powerfully in the minds of our covey of nautical fledglings. And what we were learning was, in large part, a British heritage, not to be marked just by the Prime Meridian running neatly through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, a mile or so downriver from Woolwich.

So, we set to work to learn the skills and the physical, intellectual and social conventions of the sea, all, so it was hoped, to be cemented in place during just one year’s learning ... a somewhat intimidating prospect.

That I was in a different, and in some respects, more solemn world was brought home to me on November 11th, 1960. While living in Woolwich and attending school as a dayboy, our parents had taken us to attend Remembrance Day ceremonies at the Royal Artillery barracks (located on the road to Eltham). Both parents had lamented on occasion that the Merchant Navy had been almost entirely ignored on these occasions, for they had, by living close to the Royal Docks during the War, witnessed at close hand the targeting of merchant ships, frequent and accurate bombing of the city, and the seemingly random destruction of homes and commercial structures both beside the Thames and in dockland.

At Warsash, however, some considerable way was made to recognizing this forgotten component of the Merchant Marine’s role in defeating Nazism. The whole school was bussed up to St Paul’s Cathedral and paraded in the Cathedral’s forecourt on Remembrance Day, where there was a solemn inspection, followed by our attendance in the Cathedral for a long and moving service. Being close to the time of the events themselves (recall that this was only 15 years after the cessation of World War II) allowed the very senior officers, army, navy and air force alike, and many others who had survived the War to move amongst us and for me to feel a pride that never left me. Mother was specifically pleased to be able to say to me that she felt that at last adequate acknowledgement of the Merchant Navy’s wartime role had been made, even though it had taken far too many years for that acknowledgement to receive adequate recognition throughout society.

Abridged account from Micheal Frost's Book

Michael Frost's Book can be purchased from Amazon

Comments